The enduring mystery of the Egyptian pyramids often centers on their sheer size and architectural precision, but equally fascinating is the question of the **materials** used in their construction. Imagine the logistical challenge of sourcing, transporting, and precisely fitting millions of stone blocks together. Where did the ancient Egyptians obtain the seemingly endless supply of stone, and how did they manage to move these colossal **materials** across the desert landscape to the Giza plateau and other pyramid sites? The answer lies in a combination of nearby quarries, ingenious transportation methods, and a highly organized workforce.

Local Quarries: The Primary Source

The primary source of stone for the Giza pyramids was located relatively close to the construction site. Several quarries were identified along the Nile, including one near the pyramids themselves. These quarries yielded the yellowish limestone that forms the core of the pyramids. This made transportation a little easier, as the stone did not have to travel vast distances. The availability of high-quality limestone nearby was crucial to the feasibility of the pyramid project.

- Limestone Quarries: Located near Giza, providing the bulk of the pyramid’s core.

- Granite Quarries: Further south, near Aswan, offering the harder granite for interior chambers and facing stones.

- Alabaster Quarries: Used for specific architectural elements and decorative features.

Granite and Other Specialty Stones

While limestone formed the majority of the pyramid structure, other stones were used for specific purposes. Granite, a much harder and denser rock, was employed for the king’s chamber, sarcophagus, and some of the outer casing stones. This granite was sourced from quarries near Aswan, hundreds of miles south of Giza. Alabaster, a softer, translucent stone, was used for decorative elements and interior features. The transportation of these specialty stones posed a significant engineering challenge.

Transportation Methods: A Monumental Feat

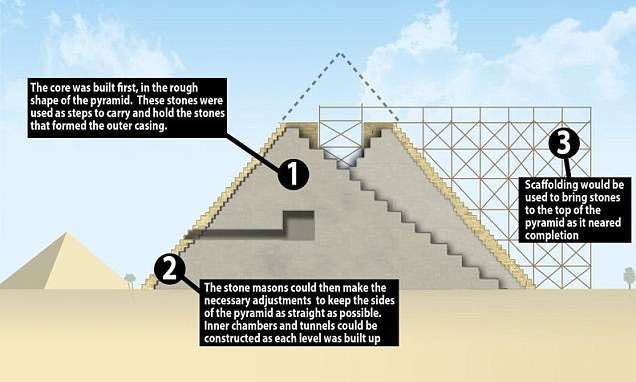

Moving massive stone blocks, some weighing several tons, required ingenious transportation methods. The most likely scenario involves using sledges pulled by teams of workers, possibly aided by wooden rollers. The ground was likely wetted to reduce friction. For transport along the Nile, barges were used to float the stone downstream. The organization and coordination of these efforts were truly remarkable.

The Human Element: Organized Labor

The construction of the pyramids was not solely a matter of **materials** and engineering; it also required a vast and organized workforce. Contrary to popular belief, the pyramid builders were likely skilled laborers and craftsmen, not slaves. They were organized into teams and provided with food, shelter, and compensation. The scale of the workforce needed to extract, transport, and assemble the stone blocks was considerable, highlighting the logistical and administrative capabilities of the ancient Egyptian civilization.

Understanding the sources of the **materials** used to build the pyramids offers valuable insights into the resourcefulness, engineering prowess, and organizational capabilities of the ancient Egyptians.

WHERE DID THEY GET THE MATERIALS TO BUILD THE PYRAMIDS?

The enduring mystery of the Egyptian pyramids often centers on their sheer size and architectural precision, but equally fascinating is the question of the **materials** used in their construction. Imagine the logistical challenge of sourcing, transporting, and precisely fitting millions of stone blocks together. Where did the ancient Egyptians obtain the seemingly endless supply of stone, and how did they manage to move these colossal **materials** across the desert landscape to the Giza plateau and other pyramid sites? The answer lies in a combination of nearby quarries, ingenious transportation methods, and a highly organized workforce.

LOCAL QUARRIES: THE PRIMARY SOURCE

The primary source of stone for the Giza pyramids was located relatively close to the construction site. Several quarries were identified along the Nile, including one near the pyramids themselves. These quarries yielded the yellowish limestone that forms the core of the pyramids. This made transportation a little easier, as the stone did not have to travel vast distances. The availability of high-quality limestone nearby was crucial to the feasibility of the pyramid project.

– Limestone Quarries: Located near Giza, providing the bulk of the pyramid’s core.

– Granite Quarries: Further south, near Aswan, offering the harder granite for interior chambers and facing stones.

– Alabaster Quarries: Used for specific architectural elements and decorative features.

GRANITE AND OTHER SPECIALTY STONES

While limestone formed the majority of the pyramid structure, other stones were used for specific purposes. Granite, a much harder and denser rock, was employed for the king’s chamber, sarcophagus, and some of the outer casing stones. This granite was sourced from quarries near Aswan, hundreds of miles south of Giza. Alabaster, a softer, translucent stone, was used for decorative elements and interior features. The transportation of these specialty stones posed a significant engineering challenge.

TRANSPORTATION METHODS: A MONUMENTAL FEAT

Moving massive stone blocks, some weighing several tons, required ingenious transportation methods. The most likely scenario involves using sledges pulled by teams of workers, possibly aided by wooden rollers. The ground was likely wetted to reduce friction. For transport along the Nile, barges were used to float the stone downstream. The organization and coordination of these efforts were truly remarkable.

THE HUMAN ELEMENT: ORGANIZED LABOR

The construction of the pyramids was not solely a matter of **materials** and engineering; it also required a vast and organized workforce. Contrary to popular belief, the pyramid builders were likely skilled laborers and craftsmen, not slaves. They were organized into teams and provided with food, shelter, and compensation. The scale of the workforce needed to extract, transport, and assemble the stone blocks was considerable, highlighting the logistical and administrative capabilities of the ancient Egyptian civilization.

Understanding the sources of the **materials** used to build the pyramids offers valuable insights into the resourcefulness, engineering prowess, and organizational capabilities of the ancient Egyptians.

BEYOND STONE: THE UNSEEN INGREDIENTS

But let’s delve deeper, beyond the readily apparent geological components. What about the unseen ingredients, the subtle nuances that whispered to the very soul of the pyramid? Consider, for a moment, the role of sacred geometry. It wasn’t merely about stacking stones; it was about aligning with cosmic forces, harmonizing with the very fabric of the universe. Did they imbue the stone with intention, with prayers etched not on the surface, but woven into the crystalline structure itself? Could the specific quarries chosen have been selected not just for the stone’s physical properties, but for its energetic resonance, its perceived connection to the divine?

THE WHISPERS OF THE DESERT WIND

Imagine the desert wind, carrying grains of sand infused with centuries of stories. These grains, swirling around the construction site, became part of the mortar, binding the stones not just physically, but spiritually. The pyramids, in this light, aren’t simply monuments of stone, but repositories of collective memory, whispering tales of pharaohs and gods, of life and death, on every breeze. Perhaps the true magic lies not in the *where* of the materials, but in the *how* – how they were chosen, how they were treated, how they were transformed from mere rock into instruments of eternity.

A LEGACY ETCHED IN TIME

So, while we can trace the limestone to the quarries near Giza and the granite to Aswan, the full story of the pyramids’ composition remains an enigma. It’s a story etched not just in stone, but in the very soul of Egypt, a testament to human ingenuity, spiritual ambition, and the enduring power of a civilization that dared to reach for the stars. The tangible **materials** tell a part of the tale, but the intangible – the beliefs, the rituals, the sheer force of will – are what truly brought these wonders to life.